On Chinese New Year's eve, when many families were gathering for reunion dinners, Tony (not his real name) was lying awake on his bed thinking about his family as he always does at night.

"Every time, you’ll be thinking for the family lah, what are they doing now," he tells me. "Eating the steamboat or what, so many things to, how to say, miss lor."

This year, Tony did not have a reunion dinner with his family.

But that wasn't new for him — it's not as if the 54-year-old celebrated any of the last seven Chinese New Years with them anyway.

Instead, he spent them in the confines of Changi Prison, where he is currently serving the last few months of his jail sentence.

Today, more than a week after Chinese New Year, the festive celebrations have more or less died down.

Tony is sitting across from me in a room outfitted as a computer lab, likely used for computer literacy lessons.

I've been invited to observe how inmates celebrate the New Year, and this will be Tony's last Chinese New Year behind bars before he is released in May.

I'm at first taken aback by the geniality of the man dressed in the white T-shirt and navy blue shorts that all inmates wear.

Inmates in the midst of a Buddhist monk's counselling — a segment of Changi Prison's Chinese New Year proceedings. Image by Andrew Koay

Inmates in the midst of a Buddhist monk's counselling — a segment of Changi Prison's Chinese New Year proceedings. Image by Andrew Koay

I can't help but note quietly his resemblance to Tony Leung — the Hong Kong actor famous for his collaborations with legendary filmmaker Wong Kar Wai — hence the pseudonym I've given him.

Like Leung, Tony's eyes appear soft and warm in their gaze, and — at least for the time that we're sitting across each other — seem almost permanently to be on the verge of a Duchenne smile.

This rougher, more rugged doppelgänger of Leung is on first impression overwhelmingly approachable; affable in a way that belies his criminal history.

"Fast money" and landing in prison

This is actually Tony's third stint in prison since 1994.

Back then, as a 28-year-old working "odd-jobs", he landed himself in an unexpected and wholly unfortunate set of circumstances.

"Due to my financial — I mean I got some problem lor. My father got stroke, and my first child was going to be birthed. So need money. So I attempted — I mean go to some fast money lor."

Making that "fast money" meant turning to theft, and Tony was eventually arrested and convicted for stealing computer parts.

He was released from prison in 1998, but found himself back in trouble with the law in 2006 for stealing cars.

Finances it seems, continued to be Tony's main motivator when it came to being tempted into crime.

Family of six in a two-room rental flat

His second sentence saw him through 2012 and by this point, Tony and his wife had four children between the ages of 21 and nine; the family of six squeezing into a two-room rental flat that was no doubt bursting at the seams.

Things finally started looking up when the family received news that they had successfully balloted a built-to-order (BTO) flat.

A brand new 4-room flat in a new estate was a chance for the family — and Tony in particular — to start afresh.

But any enthusiasm and excitement over the new place ground to a halt when Tony was informed that he would only be able to take out a loan for half the BTO's price.

Even today, Tony recalls the numbers and math effortlessly, as if they'd been burned into his mind from countless nights of ruminating on mistakes past.

"So that time ah, my wife and my CPF only got S$70,000 and the house was S$342,000. So need to top up S$100,000.

So end up I go and borrow bank money, and go and gamble lah. To go and get this S$100,000. But end up I lose S$60,000."

"Stupid right?" he says while laughing.

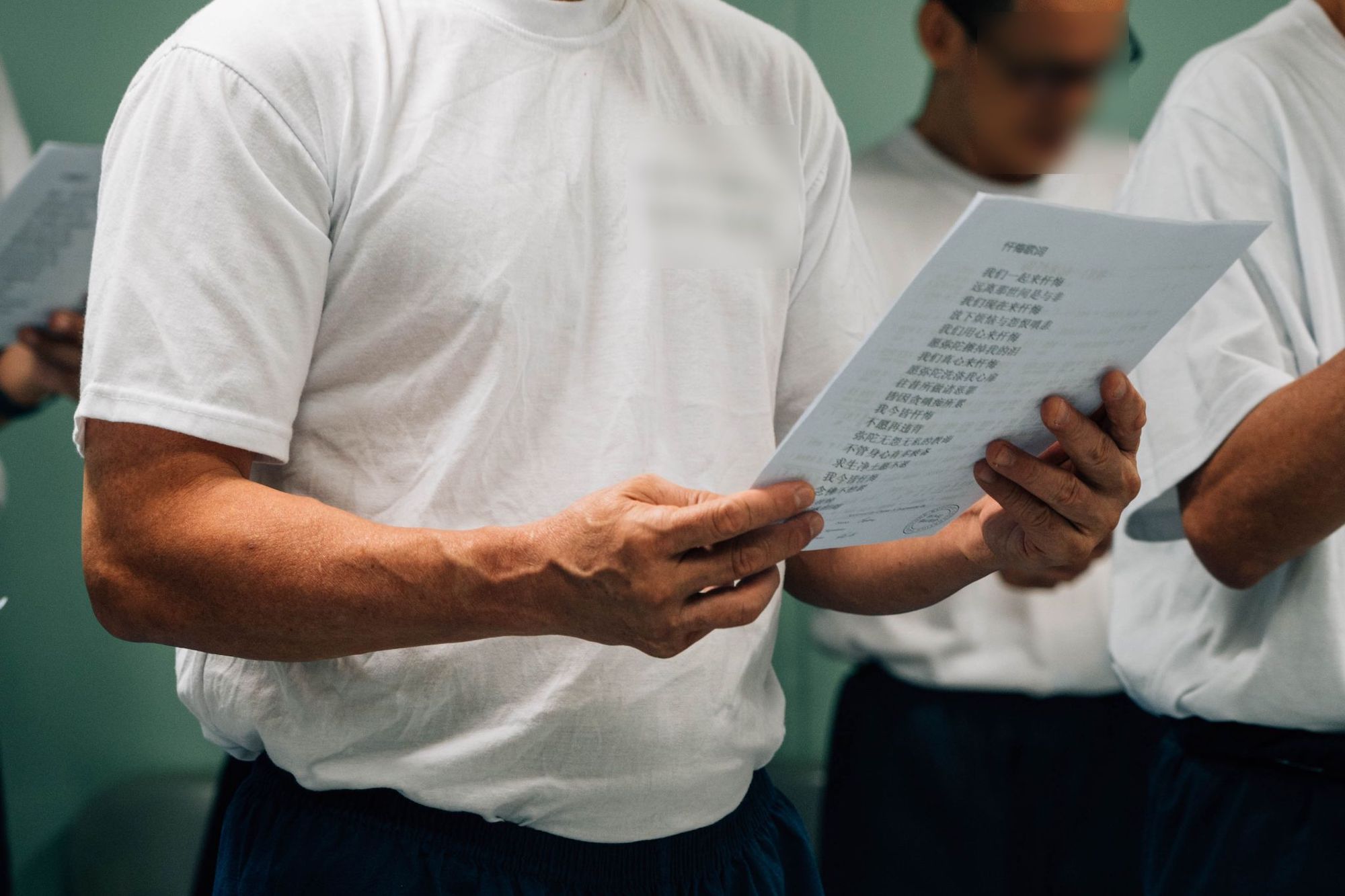

Inmates stand to sing after counselling by a Buddhist monk. Image by Andrew Koay

Inmates stand to sing after counselling by a Buddhist monk. Image by Andrew Koay

Desperate to make up for his losses, and to secure his family's new home, Tony went back to stealing cars.

He got back in contact with people who bought stolen cars — Malaysians, he tells me, who apparently have a list of cars (mainly Japanese makes) that they desire.

Once stolen, Tony would pass the cars to these buyers, who then drive them over the border.

Now if it isn't already obvious to you, successfully stealing cars in Singapore is quite a task.

Even if you set aside the abundance of security cameras all over the island, there's still the prospect of having to get away with the burgled car in a tiny state with tight border security and huge policing capacity.

Needless to say, Tony was caught, arrested and sentenced to jail from 2013 to May this year.

A 37-year-long love story

After the judge presiding over the case had read out his sentence, Tony asked for 10 minutes to talk to his wife.

"When got (sentenced) that day, my wife was alone lah. She was stronger than me.

The first words she asked me was 'you okay or not? Don’t sit until gila (crazy)'"

He's laughing as he tells me this story, but I can see behind the creases and wrinkles of Tony's smile a real sense of sorrow over the time he lost with a woman he clearly adores.

"I met her when we were 17 years old," he says.

He was a butcher at the now-defunct Fitzpatrick supermarket, where she also worked, selling orange juice.

"Every time lunchtime go sit there and I’ll disturb her lor: 'wah your orange juice, sweet or not?'

So every time disturb her then I get her lor."

Seven years later, in 1990, they were married — and, he says, she's stuck by him through thick and thin.

In fact, she visits at least once a month, sometimes twice.

His participation in one of the Changi Prison's family programmes — where inmates are given opportunities to build stronger bonds with loved ones — has also allowed him to engage in open visits.

"I got the chance to hug her," says Tony.

"Inside here very hard to get the chance to hug or touch your wife and children. So only you can participate in the programme then you got the chances for the open visit."

Parenting behind bars

Outside of an open visit, visits are either through a glass panel or video link and tend to last 20 to 30 minutes.

Just the week before, Tony's wife, along with two of his sons (the eldest and the third) paid him a visit.

It was the first time in two years that the third son, now aged 27, was visiting him.

"Very busy," Tony tells me, explaining the lack of visits. "He go to schools and teach those dancing."

I ask him about his youngest child, a 17-year-old daughter studying in ITE whom Tony tells me he hasn't seen in person for about a year. She would have been 10 the last time Tony was a free man.

She, too, has been busy with school, says Tony.

He beams with pride telling me that she's an avid volleyball player, even representing her school in the sport.

Yet, the differences in personality and interests between a pre-pubescent child and a teen on the cusp of adulthood must be large.

Parents who see their children on a daily basis already struggle with kids this age — how much more a man who hasn't been a parent to his daughter for the last seven years?

"The gap is there already," he says. "So need to go and back up back everything lor. It’s not easy lah, it's not easy. They visit me with a glass panel. It's different when you go outside every day."

However, he doesn't seem too fazed by the prospect of having to start parenting again, laughing when I ask if he's worried about her having boyfriends and all the other things that come with being in what Tony himself calls the "rebellious age".

At the moment, he's more preoccupied with the physical changes that his children have gone through — understandable for a parent whose opportunities for contact with them are few and far between.

"Last Wednesday, my eldest son and my third son come, they update me that their younger sister is very tall. So I always ask my wife to arrange face-to-face (visit), cause I wanna see how tall mah. I cannot see — she don’t wanna come. Also she very busy lah, that’s why."

I suppose the tougher realities of what it will be like to be a full-time parent will hit a few months down the road, but right now, mere months before his release, Tony's overwhelming emotion is understandably excitement.

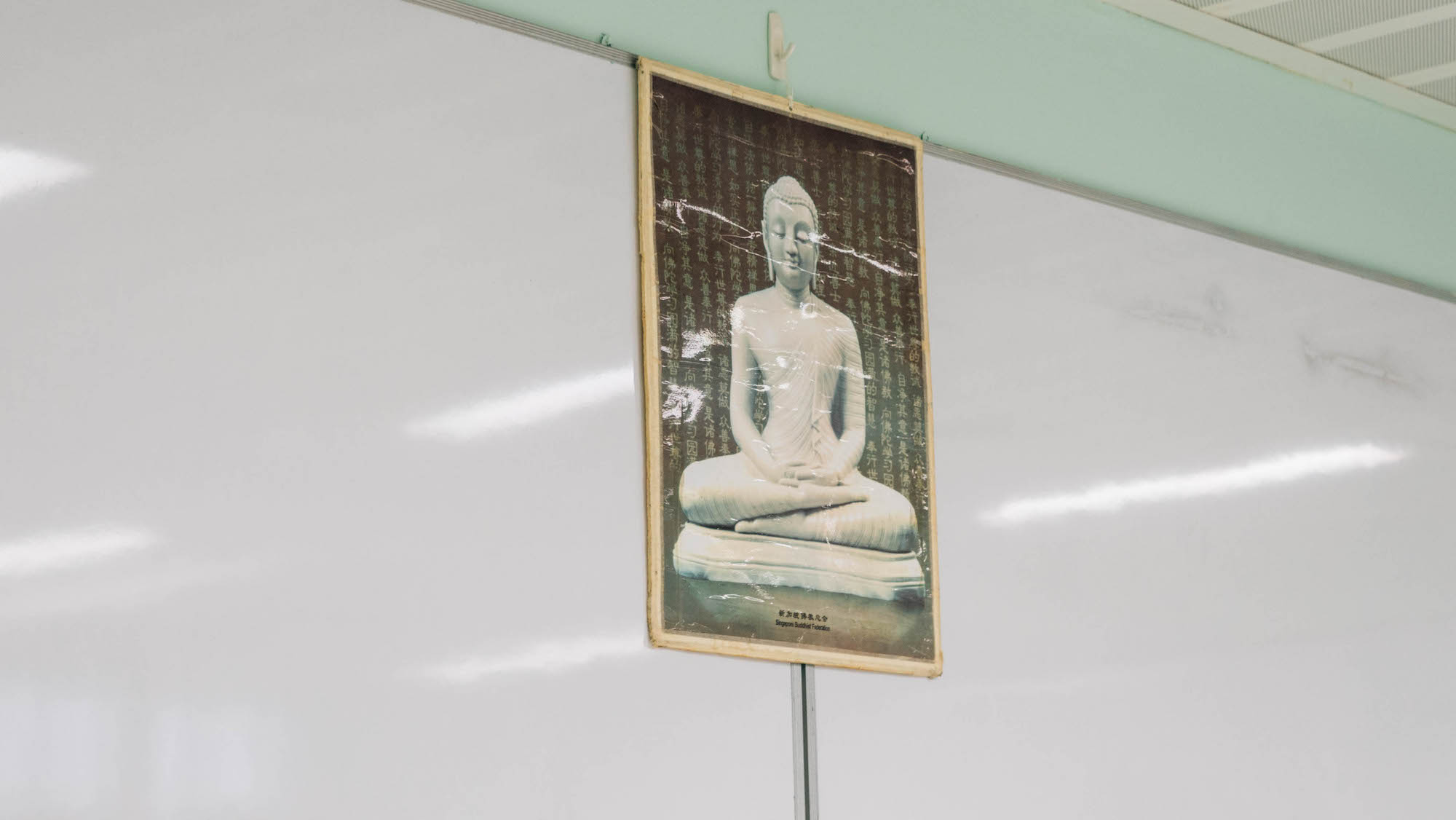

Chinese New Year in Changi Prison seems largely a Buddhist affair. Image by Andrew Koay

Chinese New Year in Changi Prison seems largely a Buddhist affair. Image by Andrew Koay

Eating pork, holidaying in Malaysia

He tells me that the first thing on his agenda will be to have a meal with his family: "pork," he says between laughter.

"So many years never eat pork already!"

The next thing on the list will be to pay respects to his mother and his mother-in-law at their houses.

Then, his grand plan.

"Yeah lah, have to bring them go holiday lor. Stick with them.

Start with Malaysia first lor."

There's also the small matter of staying out of trouble.

For this, Tony has two different options in mind to keep himself busy: he's either going to work as a Grab driver or as a hawker selling lor mee.

Whatever it is, his wife has made it clear to him that finances are not something she wants him to stress over.

"My wife told me 'I don’t want you to get so many money, you know? I just want you all the time beside me.'"

Celebrating with counselling and some songs

Today, Chinese New Year celebrations are underway in Changi Prison.

Rather naively, I imagined inmates eating yusheng or getting angpows.

Image by Andrew Koay

Image by Andrew Koay

The reality was that prison proceedings are far more understated. They involve inmates getting some snacks and oranges before getting counselled by a Buddhist monk.

I'm later informed that Chinese New Year is designated as the one holiday that Buddhist inmates get to celebrate.

My rudimentary understanding of Mandarin tells me that the counselling has something to do with the rat — no surprise, since it's the Zodiac animal for this year.

While it may look nasty and is shunned by many, the rat is actually quite a good and clever animal, says the monk (but don't quote me on that).

From my seat in the corner of the room — which appears to me as a very plain and sterile classroom — I can see Tony sitting back in his plastic chair, arms folded, listening intently.

The corner of his lips are slightly curled upwards in a quarter-smile, as the monk tells the room that inmates shouldn't let their past stop them from being useful people.

When the counselling comes to an end, sheets of paper with lyrics are passed around the room and the inmates rise to sing a few songs, a capella.

I don't quite understand what they're singing, but I find myself moved by the ebbs and flows of their baritones.

Dreaming of giving back

As I leave the room, midway through proceedings, Tony leans backwards in his chair to catch my attention.

The 54-year-old flashes a good-natured grin and waves goodbye to me. I return the gesture before the door shuts behind me.

Tony singing along to the Buddhist songs. Image by Andrew Koay

Tony singing along to the Buddhist songs. Image by Andrew Koay

In a few minutes, I would have walked through multiple steel-barred gates and taken a lift down a few floors, before exiting Changi Prison.

Tonight, I'll be having dinner with my family before settling into my own bed.

Tony, on the other hand, will be in his cell, lying awake and cycling through the thoughts that come to him every night.

No doubt his mind will drift to his kids and then his wife, who he tells me has been his compass as he navigated life in prison.

"At first starting — I was sentenced the first day ah — come inside here, I don’t know how to pass the day. Luckily my wife supported me lor. She visit me until now ah, never give up."

There's a good chance he'll pause for a moment and consider her warning to him as well:

"She said ‘No more. Another time ah, we’re all missing already. We’ll leave you'."

As he closes his eyes and drifts off to sleep, perhaps he'll dream of what life will be like outside of jail.

Perhaps his thoughts will rest on the same day-dream that he has every day:

"This will be a dream for me to do something back for my family, to the society as well. That will keep me moving forward, to be strong."

Stories of Us is a series about ordinary people doing extraordinary things. Be it breaking away from conventions, pursuing an atypical passion, or making the world a better place in their own small way, these stories remind us both of our individual uniqueness and our collective humanity.

Top image by Andrew Koay

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.