Farah is probably the most interesting friend I have.

She's only 20 years old, but her life has been surreal.

We first met in 2016 during our time in polytechnic, and we've gotten really close since then.

I knew bits and pieces of her past life but never the complete story, which bugged me a lot because I was always so intrigued by her.

I mean, if you go to someone's house and they introduce their uncle as "the former drug addict", you'd surely want to know more too.

Farah kept telling me that her life was boring and average, but when I begged her to show me her old house near Geylang, I knew right away it would be anything but.

Dirty environment

Farah says she lived in the Geylang flat from the age of 11 to 15.

At first glance, the HDB block looks perfectly normal. It's upon closer inspection that you realise it's not your typical neighbourhood.

It was subtle, but the signs were there.

Rubbish strewn everywhere and the entire place reeked of cigarettes, booze and, well, garbage.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The residents I saw there were mostly older, and the strong smell of their medicated oils formed a discomforting mix with the other already-pungent odours.

"My mother would hold her breath whenever she entered the lift because the smell was worse there," said Farah.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

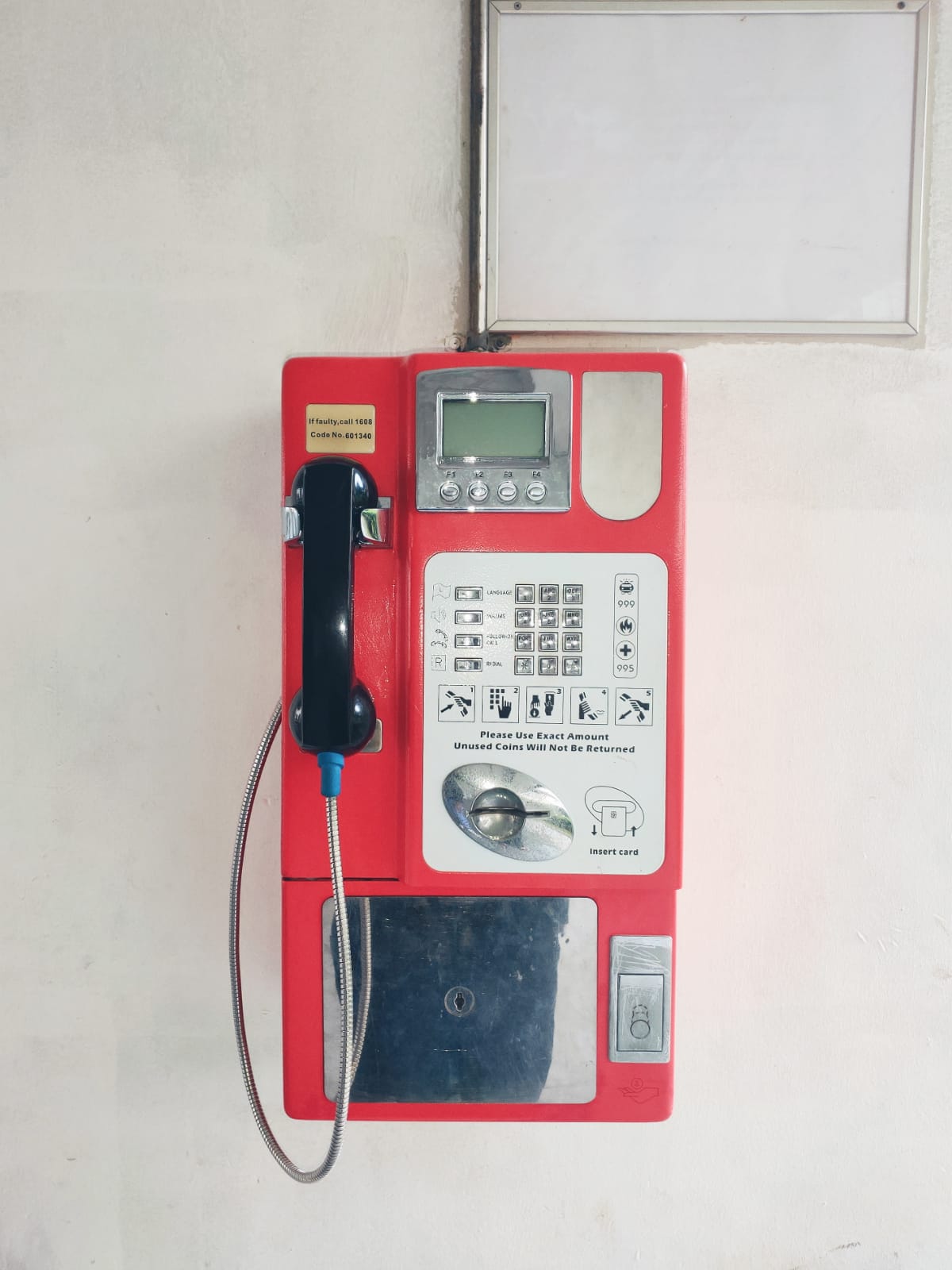

I notice that the block also has a payphone. I can't even remember the last time I saw one of those.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

"That's how poor the people here are. When I lived here, there would always be a long queue for the payphone every day."

Farah stayed in the neighbourhood between 2010 and 2014 — when, if you might recall, the iPhones 4 through 6 were launched.

But Farah told me that she had but an old, small Nokia phone and her house didn't have any wifi.

One question kept running through my mind as we walked around the area: how did she end up there?

Parents divorced

It all began with her parents' divorce in 2007, which she somehow never found out about in the few years that followed.

Farah says her mother was also struggling financially and could not buy her own house, so the broken family continued living under one roof, she and her younger sister being none the wiser.

Three years later, though, her mother married another man and got a job as an administrator, allowing her to buy her own flat — "the Geylang house", the term Farah uses to refer to it.

That, she says, was the only place her mother could afford at the time.

Although Farah and her sister followed their mother, the initial agreement was that they were allowed to visit their father whenever they wanted to.

But soon after they moved, their mother refused to let them stay at their father’s.

"I was very angry and frustrated with my mother for not allowing us to visit our father. Sometimes I still am.

However, now that I think of it, I realised she felt very alone and needed us to be her moral support in this time of change."

Things only settled down after a year and they were finally allowed to freely see their father.

Six people in one small house

The titular Geylang house is a one-room rented studio apartment.

Today, Farah's grandfather is the current owner of the house.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The corridor outside the house. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The corridor outside the house. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

But back then, Farah lived there with her mother, sister and stepfather.

They also hired a helper after a while as her stepfather had two children from a previous marriage that would stay over sometimes.

His children both had autism, so more help was needed to manage the house when they were around.

In 2013, her uncle (yes, the former drug addict) came to live with them too.

So that meant six people, all in one small, incredibly cramped one-room flat.

The cramped walkway from the kitchen to the living room. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The cramped walkway from the kitchen to the living room. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The house didn't have a bed, and there was only one bathroom.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Farah shared a mattress with her sister in the room and the helper slept on another mattress beside them.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Her mother and stepfather slept on a mattress in the living room.

Her uncle got the couch, although he often slept in the driver’s seat of his car, with the window slightly down.

Since there were so many people sharing one small space, the lack of privacy and comfort led to frequent arguments.

It didn't help that Farah, being the rebellious daughter, always had a knack for calling out her mother's faults.

The fight would start with her mother being annoyed at little things — an out-of-place bag or Farah and her sister laughing too loudly.

It even became a recurring inside joke between the sisters.

Each time Farah and her sister started laughing, they would say to each other jokingly: “Cannot laugh so loud because mummy said happiness is a sin."

Drug users and drug raids

Despite it all, the small house and her familial issues were the least of Farah's problems.

Stuck in a low-class neighbourhood, crimes were prevalent.

"It's not as bad as it used to be because a lot of effort was put in to make the area safer for people."

Farah even sent me a link to an article that reported the measures implemented to rid the area of crimes.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The back of Farah's HDB block. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The back of Farah's HDB block. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

When she lived there, however, she says she was used to seeing drug needles lying around the staircase and corridors.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Apart from her uncle, Farah says many of the residents in the area were also drug addicts.

Some of them were in jail while their children stayed in the flats alone. Some hadn’t been caught.

Her uncle had just gotten out of prison when he came to live with them.

"My sister said it was like making a recovering alcoholic live in a bar; we might as well give him the drugs — that shows you how many drug users lived in the vicinity."

Drug raids often occurred in the area too.

"A makcik used to update my mother on the day’s events because her sons were friends with the drug users," Farah told me casually.

The makcik who lived next door to Farah's family was very close to them. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

The makcik who lived next door to Farah's family was very close to them. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Farah also tells me she believes she often saw officers in plain clothes roaming her neighbourhood.

She said it was easy to spot them as they were always well-groomed and wore new shirts. They also usually travelled in pairs.

Farah's family flat wasn't spared from the drug raids either.

She recalls that once, Central Narcotics Bureau (CNB) officers raided her house as they suspected that her uncle had taken drugs again.

Fortunately for her, she happened to be at her father's house at the time.

Her mother, on the other hand, was left alone to deal with the mess.

"She called us crying about it.

First, she was already afraid that there would be something she didn’t know about and second, the CNB officers left the house in a mess.

They didn’t find anything and my mother had to spend the day cleaning up with my helper."

Blood stains from gang fights and signs from loan sharks

Drug addicts weren't the only criminals living in the neighbourhood — gang members and loansharks were ever-present as well.

Many fights broke out in the area.

Nearly every night, Farah and her sister would hear the echoes of men shouting and glass bottles shattering.

The next morning, they would find blood stains at the lift lobby.

"Sometimes, there was blood in the lift and once, when we reached the ground floor, there was a trail of blood leading us to a nearby bench. It was also stained."

Even when Farah and I visited the area, I could see remnants of blood stains on the floor and in the lift.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

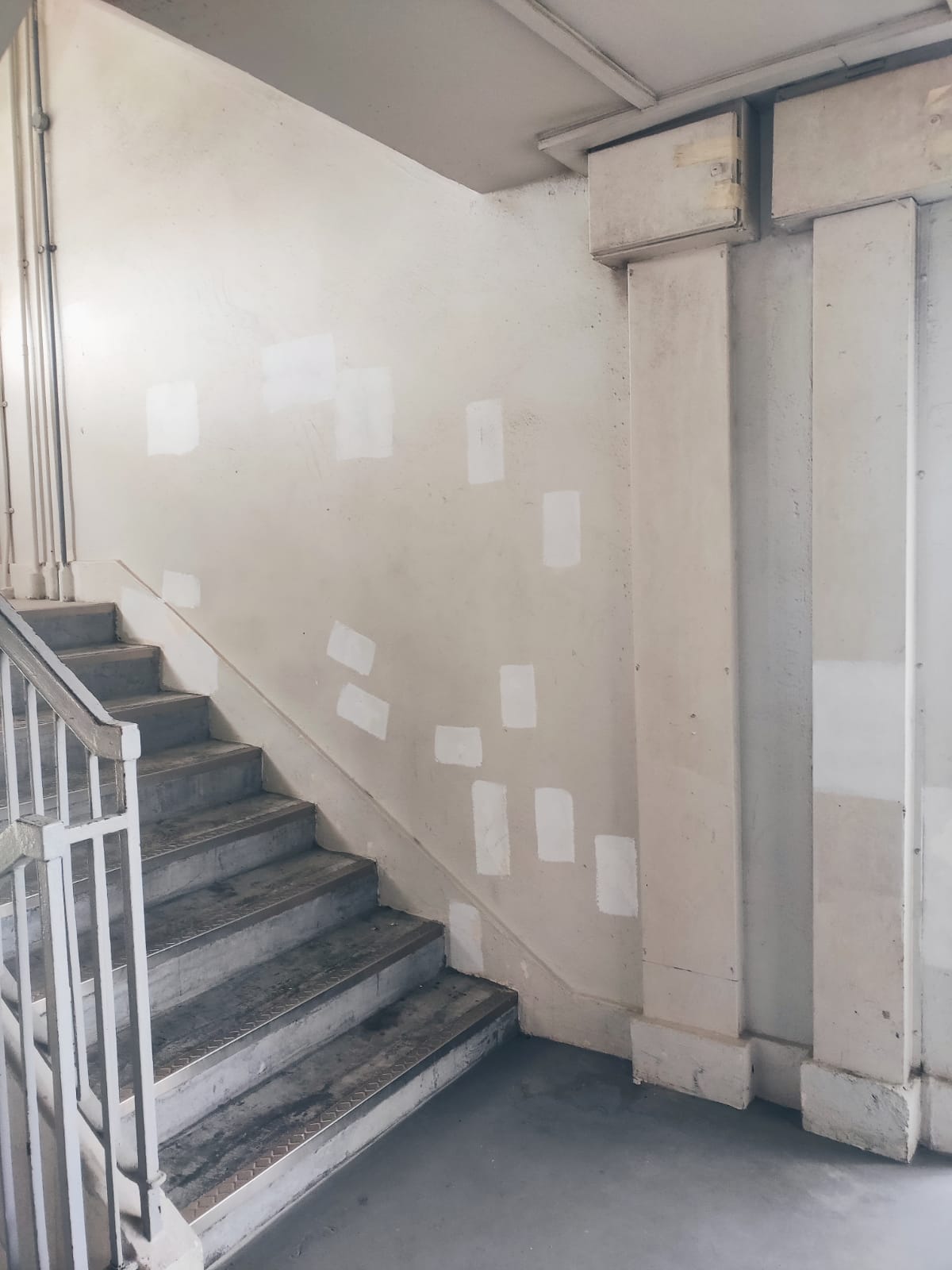

If it wasn't blood smeared on the walls of the block, there would instead be that familiar 'owe money pay money' adage crudely painted on.

The specific messages were no longer visible, although evidence of their existence remains.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Suicide cases

Farah shares that the struggles of living in a troubled area like this had even worse effects on some of the residents.

Suicide attempts were frequent, she says.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Farah recalls witnessing one when she was only 12 years old.

"I remember looking out the window and seeing many policemen and a crowd of people at the foot of the block.

I didn't know what was going on until I realised they were looking up and shouting.

I knew I didn't want to witness anymore of it so I went to the room furthest away from the windows, the living room, and just watched MTV like nothing was happening.

After about two hours, I remember going to look outside again and the area was cordoned off.

The crowd was gone but I saw officers wheeling a body bag on a stretcher into a black van."

Farah's mother even forbade them from walking along open walkways because there was always the possibility of someone jumping.

Farah says her mum barred her and her sister from walking along here as people often attempted suicide from this side of the block. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Farah says her mum barred her and her sister from walking along here as people often attempted suicide from this side of the block. Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Had a hard time dealing with life

Having to face so many harrowing events on a daily basis also took its toll on Farah and her family.

"My family broke down nearly every day.

I used to cry the most because I am the most emotional b*tch that has ever existed on the face of the earth.

My sister did not break down but the lack of privacy and freedom took a toll on her slowly.

In the years that we lived there, I think she suffered more and now has a lot of trauma from the house and the place itself."

On top of that, Farah says she also faced some discrimination in school because of her background.

She went to what was considered a "good" primary and secondary school.

Most of her schoolmates were of higher socio-economic status and they were aware of Farah's background.

Once, her classmates came over to her house to do a group project but one of their grandmothers' kept warning them not to go to her house.

"When they got there, there wasn’t much of a problem after all."

Farah was also one of the few students who were on the school's Financial Assistance Scheme (FAS).

She tells me she didn't really mind the fact that she wasn't as privileged as her other schoolmates, but she did get envious whenever the school conducted excursions.

Her friends could all pay for the outings. She couldn't.

"I always got scolded for ‘forgetting to bring the form’ when actually, I didn’t have the money to pay for it."

Studies were never compromised

Regardless of the challenges, Farah got through her school years with ease and obtained good academic results.

Ironically, she credits her experiences in the Geylang house for her success.

Her experiences allowed her to pick up useful skills, which she feels translated into her studies.

I've always known Farah to be a master problem solver, and I've never seen her back down from a challenge.

Besides that, the constant danger she was surrounded by inadvertently trained her to be cautious, observant and meticulous — skills that she feels also helped in her schoolwork.

Even after her family moved out from the Geylang house in 2014, Farah continued to do well in her studies.

"My stepfather saved enough money to move to another house, which is the house I am living in now.

My helper stopped working with us and my uncle went back to jail because he was taking drugs again."

Farah and her family now live much more comfortably in a four-room HDB flat in the north-eastern part of Singapore.

She graduated secondary school with an L1R5 of 11 points for her O-Level exams.

Now, she tells me she's planning to study law.

"I enjoy learning anything and everything, but I chose law to better help other people.

It's an idealistic dream but at least if anything were to happen to my family, I would have the funds and knowledge to give them a hand."

Would never change her past life

Despite her challenging childhood, Farah tells me she wouldn't change anything about it.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

Photo by Syahindah Ishak.

She also treasures the sense of camaraderie that her neighbours in her block had.

It was an unusual bond, but a bond nonetheless — one she tells me she will never forget.

"The neighbours looked out for each other. So in that sense, I was safe.

I also know that despite their thuggish exteriors, most of the people there did not want to harm anyone, especially children.

They would go about their business silently.

In fact, most of them respected my family as we were friendly and did not judge them.

I enjoyed the life I had and saw it to be normal. I didn’t think I was less privileged because of where I lived.

Farah told me she learnt to take things in her stride, and find joy even in harsh situations she found herself in.

To find happiness, even though it might be a sin.

Top photo by Syahindah Ishak.

If you like what you read, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter and Telegram to get the latest updates.